Theory of flying airplanes – good online reference

Close Calls #1 – Ballooning

I’ve decided to start a new series I call Close Calls, where I describe scenarios I’ve experienced in my 3000+ hr flying career (all VFR), that had me thinking about what went wrong. None of these situations have resulted in crashes, but all of these could have.

Today’s close call happened at the 2012 World Gliding Championship at Uvalde, Texas, where I was towing with our club’s Piper Pawnee.

There were 100 glider contestants from all around the world and a tow operation like clockwork was the goal. So short landings next to the starter field were in order. We would side step during the roll out in front of the field onto the runway, wait for the two rope hook-up and full throttle off again for the next tow. I was on the second or third tow, when I was coming in slightly slow, eyeing the taxiway across in front of the landing field next to the concrete runway. I tried to milk it in across the taxi way, when I got hit by a gust which slammed me on the ground in front of the taxi way. I immediately sensed a strong upward acceleration, like on a trampoline, resulting in the airplane pointing 30 degrees nose high into the sky at close to zero airspeed. The sloped terrain in front of the taxiway I crossed had catapulted me back into the air, but without airspeed! I was terrified and slammed the throttle all the way forward into the wall, hoping that the 260 horses would wake up in time to save me from a great embarrassment. And the reliable O-540 did what it was built for. It pulled through and the well mannered Pawnee was hanging off the propeller at full power in 30ft, slowly regaining speed and lowering the nose. I executed a go-around and landed uneventfully shortly after. Learning: carrier landings are just that: coming in too short is not an option. Keep up the speeds and be prepared for gusts. Don’t get too eager to show off the shortest landing in front of a crowd.

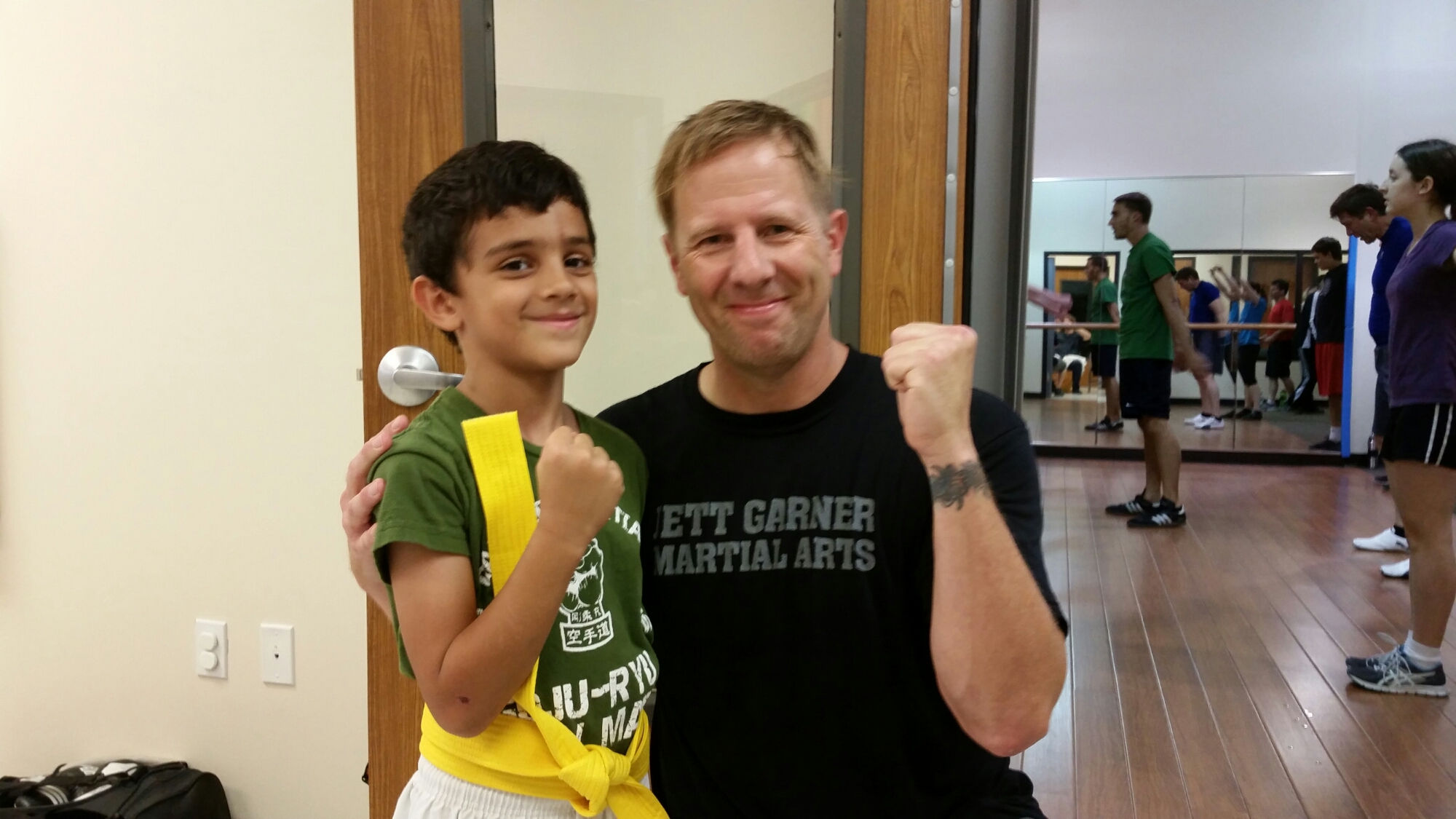

Ro’s new stuffy DIGGY that he won

Cross Country flying

After musing over VFR X-country technique during yesterday’s flight to Mustang beach I realized that I haven’t blogged about it before. So here it goes:

VFR X-country flying can be very powerfull and the freedoms enjoyed from it are amazing.

You have to stay flexible on time and routes chosen. With onboard XM real-time weather and GPS, there’s really little excuse why not to embark on cross-country adventures – even when the weather is somewhat iffy.

I view VFR cross country as risk management. You always have to have multiple plans in play but firmly commit to one of them at all times. Also, alternatives should be part of the original plan. For example, when you plan long X-Country legs with pre planned lowest Avgas fuel stops, be prepared to find an empty or non-functional pump and have another fuel airport within a safe distance available. With good cell phone coverage everywhere, I’ve found it beneficial to call ahead the next airport from the previous fuel stop to make sure they are open and fuel is available. Having them expect you to arrive also makes for a faster turn-around on the ground usually. It also gives you the opportunity to chat with a local about any special advisories for the airport.

With GPS and an auto-pilot, the PIC has a lot available time on his/her hands to do scenario planning en-route. Tasks I usually do while leveled and leaned out are: double check XM weather for ideal cruising altitude for wind. Does the experienced wind match the forecast? Adjust accordingly. Go fast into a headwind, go as slow as you can tolerate with tail winds (that’s McCready theory applied to powered planes). I also check ATIS and AWOS station ahead enroute. Either by radio when in range, or via G396 with XM weather, where all TAFs and METARs are updated regularly. I also check the movement of any significant weather in the area that might affect the flight path. Will I be trapped in bad weather after landing? Would it make sense to go behind a line of bad weather at the cost of extra time/distance?

Plan your departure/arrival times carefully. When arriving around sunset I prefer to arrive 30min after sunset. That avoids the usual evening VFR rush as well as avoids the visibility problems from a low sun on final. Also the lower temps after landing are a welcome side-effect.

Departures early in the morning will allow for shorter take-off distances from a lower density altitude and a faster climb to cruising altitude. It also allows to fly on top of Cu clouds which are low in the morning. In the afternoon, Cu tops can reach mid 15,000-20,000ft and make flying “VFR on top” unfeasible.

I usually try to fly as much with the auto-pilot as possible. That off-loads me and gives me more mental bandwidth for planning and scanning the sky.

I keep a detailed log of the flight progress. Notes include engine time at refuel, time of fuel tank switches, time at landmarks and assigned/flown altitudes with temperature and wind component.

I try to plan my fuel stops to be quick and efficient. Low price 100LL is the first consideration, a good FBO a second one. Uncontrolled airports preferred, since I can usually get in and out direct without flying a pattern. When flying in high terrain, it pays to land at the highest airport that you can tolerate for density altitude and runway length. That way your time for descent and more importantly to climb back to cruising altitude are shorter. You can save some 15min that way.

On long cross country flights I also stress creature comfort. That means traveling with plenty of water, lots of peeing bags (so my legs are defined by fuel capacity, not bladder capacity) and food and snacks. I usually carry a cooler behind the co-pilot seat with easy access for me. It also helps to keep a wet towel with the ice inside the ice chest. I use that for poor man’s air-condition during descent/taxi and departure on hot days. I’ve found that to work exceptionally well and it’s very refreshing.

Noise dampening is another creature comfort that matters on long trips. I usually wear ear plugs under the noise cancellation head-set. That makes for a very nice and muted engine humm. The lower the noise level the less fatigue you’ll experience during long cross country flights.

For the same reason I do not wear sunglasses that stick their frame under the head-set’s ear muffs. I’ve found them to cause me headaches and also reduce ANR effectivity. Instead I have a pair of glasses that I wear with a rubber band around my head – more like swimming goggles.

Back to actual flying. As I said I value options. There’s no shame in setting the plane down and to regroup when things start to look ugly. But I always make a point to try to go, but if the weather is worse than advertised I have no problem returning and waiting some more on the ground.

And here’s another guiding principle that I’ve found useful for XCountry flying: “Keep it boring”. That means the airplane should never get ahead of the pilot. Keep things nice and calm and if you can’t then slow things down. If you can’t then land. IT’s a powerful concept and it’s easy to execute in any situation other than an emergency. But for that we have training and I won’t cover it here. So keep in mind that “boring is good” if it comes to cross country flying.

Back to risk management. On one recent flight I had to depart from 2 hours away from the destination and reach in time before sunset. So there was a little pressure to complete the flight on time and fly a bee-line straight to the destination. The problem was I didn’t have a functioning GPS onboard and the area was sparsely populated. I also had minimum fuel when I arrived at the departure airport. I chose to take extra time to get extra fuel to have more options in the air (the plane was night VFR legal, but really all you need is a red flash light and a functioning landing light). Then, when I departed with 5min to spare, I had the choice of dead-reckoning direct with few land marks or follow roads for 10NM extra. I chose the latter, put the right wheel on the road and cruised home in a relaxed fashion – knowing there wouldn’t be much of a risk of loosing extra time from loosing my way. I made it home in time – but more importantly with peace of mind along the whole way because I had options. I could have easily landed at a night airport alternate close by if I hadn’t made it in time. Options is key.

Same for possible mechanical malfunctions with the plane. It’s nice to refuel enroute at an airport that has an A/P. Why? Because once I landed in the middle of no-where I had a flat tire. Getting a new tube mounted took a day. It would have been faster with professional help. And worse things can happen. Magneto, vacuum pump, battery, tires all have failed at one point or another during trips. Having options helps. And of course flying VFR doesn’t require a vacuum pump…. 🙂

I like flying high – because if gives me time and options if the engine quits. From 9.5k ft or 10.5k ft it’s not a scary thing. The only downside from flying that high would be a fire emergency. Those are extremely rare and I’m OK with that risk.